Natural Science - Year I

Unit 1: What is Science?

History Weblecture for Unit 1

| This Unit's | Homework Page | History Lecture | Science Lecture | Lab | Parents' Notes |

History Lecture for Unit 1: Introduction to Natural Science

For Class

- Period: Fall Semester covers pre-history through the Roman Empire.

For the interactive timelines, click on an image to bring it into focus and read notes.

Click on the icon to bring up the timeline in a separate browser window. You can then resize the window to make it easier to read the information.Click here: Timeline PDF to bring up the timeline as a PDF document. You can then click on the individual events to see more information if you want. Exploring this version of the timeline is optional!

- Geographic Location: All

- People to know: None

- See science topics: Topics and Limitations

Outline/Summary

- Reading for Meaning: Concepts and Methods

- Assumptions for this course

- Study/Discussion Questions

- Further Study

Reading for Meaning: Concepts and Methods

Let's start by defining the time period we will cover for the fall semester: pre-history which archaeologists date from early fossil records of humans (1 to 3 million years ago) to about 100000 years bce ("before the common era") when people began writing. We'll follow the development of science from the prehistorical period to around 200 ce ("the common era"), and in the spring we'll take up the Medieval and Renaissance periods of Western science, with a side trip into the gold age of Islamic science.

Note that we even name our historical periods depending on prevailing opinions. We used to call these periods "Before Christ" and years since zero as "the Year of Our Lord", but there are problems with this simply because there is debate over exactly when Jesus lived. So we agree on a certain year as the common "zero" year and count backwards and forwards from that year.

What is Science?

In order to discuss the history and methods of science, we need to define what we mean by science.

The word science comes from the Latin scire, which means "to know", but there was originally no limitation on what was known. Aristotle used the Greek word we translate as "science" to mean all information or wisdom or data, that is, anything that was knowable. All philosophy was part of this body of knowledge, and the part that dealt with the natural world became known as "natural philosophy".

All information has to be organized in some way so that people could learn it. The most basic sciences of the ancient world were arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy, which had to be mastered first and which formed an introduction to all other areas of knowledge. In the middle ages (roughly 400 - 1400 ce), the "division of sciences" was the organization of all knowledge into separate disciplines or teaching areas, and it included everything from theology (the highest science) to agriculture (a basic practical science). Sometime in the eighteenth century, people began to use "science" to mean that information which they thought could be known with certainty: objective, measured knowledge about natural phenomena, verified by the application of a special scientific methodology. Other forms of human experience, such as divine revelation or poetic inspiration, might be valid sources of information to the individual, but because they were subjective and personal experiences, they couldn't be verified and so are not considered scientific knowledge by this modern definition.

Organizing Knowledge

The human mind is built to organize the sensations it receives into forms that it can identify and remember. The methods of learning and creating knowledge in forms that we can discuss with each other and leave as legacies to our descendants follow similar processes whether we are discussing information about an historical event, a poem, a major scientific theory, or yesterday's Dilbert cartoon. When we encounter new experiences or phenomena, we tend to

- Look at the characteristics of the thing itself. What characteristics depend on the identity of the thing itself? What characteristics change with the amount of the thing?

- Which characteristics are essential and identify it as this type of thing and not something else? Which are accidental and identify it as this particular thing, and not some other instance of the type?

- What similarities does the thing have with other things?

- What categories of things can we make (and stick this one in)?

- Is the thing an object or a process?

- If it is an object, can we break it down into components?

- If it is a process, can we break it down into sequential steps?

- In a collection of similar things, can we find a pattern, either a repeated shape (pattern in space) or a repeated series of steps (pattern in time)?

- Is there a cause—effect relationship between this thing and something else?

- Can we put this thing into some framework of categories and/or processes?

- Can other people experience the object or event as we do?

Click on an image below to explore these questions further.

This last question moves our analysis of the object or event from something we experience by ourselves to an experience that we share with other people. Since the eighteenth century, science in western civilization has been primarily concerned with objects and events that can be experienced objectively, that can be observed independently in the same way by many people. Using an objective approach, we can identify characteristics for something and different people can measure these characteristics and compare their findings. When the findings agree, we assume that the measurements accurately reflect reality, and that the observations have been verified.

Suppose that I look at a leaf objectively. I can measure its size and describe its shape. I can break it down into components like cuticle, veins, and mesophyll tissue, or even more basic structures like organic molecules, or even atoms, and count how many of each type or present. These characteristics persist whether I observe the leaf or not. If other people measure the size and shape of the leaf, or count the molecular or atomic components, their measurements and calculations should be close to my own.

I can also look at the leaf as a metaphor for life, or an symbol of spring. This is another and valid way to experience the existence of the leaf in my life, but I can't share this experience in the same way that I share my count of the number of oxygen atoms. The experience of the leaf as a symbol of life is not inherent in, or part of the leaf itself. Another person might look at the leaf and see it as a symbol of transience. This kind of experience is subjective, and is produced by my mind; it exists only as I think of it.

One of the questions that we need to explore is whether the eighteenth century philosophers were right in claiming that science should be limited to objective knowledge, or even whether purely objective knowledge is possible!

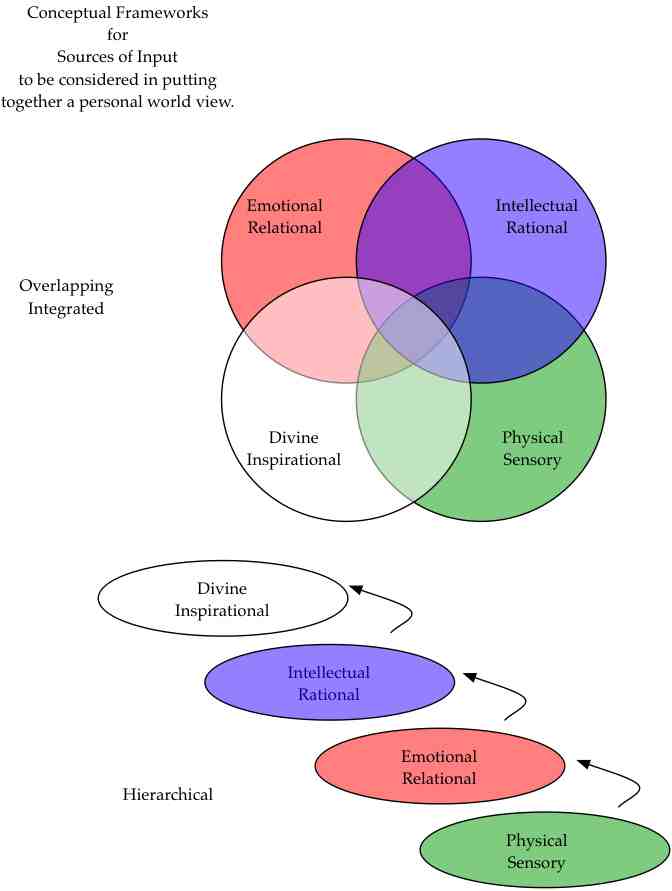

Conceptual Frameworks

Once we start building up a body of knowledge and show relationships between different pieces of the body, we are creating conceptual frameworks that allow us to quickly identify and deal with information. These frameworks are absolutely necessary, but they also have drawbacks.

Despite the standard scientific claim to objectivity, human experience is always colored by a "conceptual framework", the intellectual and emotional baggage we bring to any experience and which we use to classify, examine, and eventually remember that experience. We each have our own conception framework, and we try to stuff our experience into it the way we stuff our clothes into a suitcase for a long trip. Our frameworks control, to a large extent, how we interpret the events around us. Since my framework is the outgrowth of my personal experience, and formed to some extent by my identification with particular groups (family, religion, nationality), and by my own agendas, I may interpret an event quite differently from someone else, even though we agree on the facts of the event.

For example, my Canadian coworker wished me well as we left work for the 4th of July holiday, hoping that I would enjoy the celebration of my country's "rebellion". I don't think of the War of Independence as a rebellion (which has bad connotations, as in "rebellious teenager"), but as a revolution (replacing something bad with something good); but then, I've been indoctrinated by years of history taught by patriotic American teachers. My coworker, on the other hand, went through the Canadian public school system, taught by patriotic Canadians who still see their Dominion as under the titular if not practical authority of the British throne. My "American revolution" is his "colonial rebellion".

We all have these frameworks, or intellectual suitcases, in which we carry our own often very personal ideas of life, the universe, and everything. Every time we encounter a new experience or new idea, we decide whether to throw it out or try to stuff it into the suitcase. If we can it to fit into our current suitcase, we don't have to work to close the case and continue on our journey. But if the new experience doesn't fit, then something has to give way: either the suitcase, or something already in the suitcase, or the new experience.

Here is a more controversial example from the field of science: the modern theory of evolution does not fit into everyone's conceptual suitcase easily. For many people, the concepts of Creation and Evolution are both too big to fit into one suitcase: these people would say that the two theories are mutually exclusive. Some people solve this by throwing out evolution as a viable explanation, others by throwing out strict Biblical Creationism as a viable explanation. There is a third possible course of action: some people throw out the suitcase and try to get a different one that can accommodate both concepts. The method you chose to resolve such a dilemma depends on your suitcase, that is, on the concepts and values you use to organize your spiritual, intellectual, and emotional experiences. One of our purposes this year is to look at our conceptual frameworks, so that we can better understand why we accept some scientific ideas and reject others.

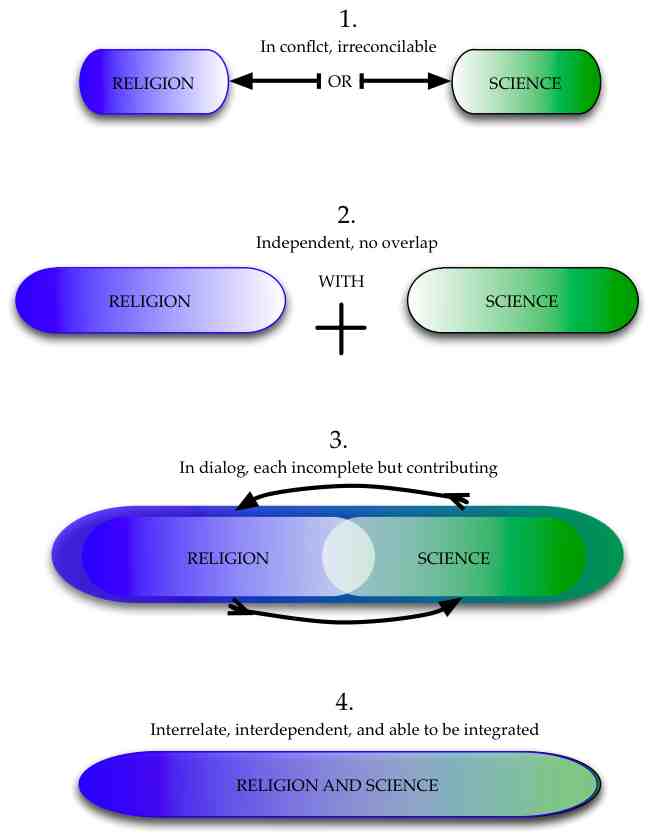

Of course, the question of Evolution vs. Creationism can lead to the larger question: what is the relationship between religion and science? It may help our discussion to lay out some options. Looking at different discussions about religion and science as ways of looking at our world and our experience of it, there appear to be four major possibilities:

- The two approaches are in conflict. They deal with the same materials and issues, but contradict each other on key points, and they cannot be reconciled. This relationship implies that each adheres to different principles and accepts different forms of evidence and authority.

- The two approaches are independent, non-overlapping areas of inquiry that do not conflict but also do not intersect one another. Each has different principles and authorities, but they deal with separate areas, so there is no conflict.

- The two approaches are in dialogue with one another, each contributing to a complete picture. This relationship implies that neither provides a complete world view or explanation of human experience. Where they do overlap, they do not contradict but support one another.

- The two approaches can be integrated into a single world view where each is in sympathy with the other. They share similar goals in explaining the whole of human experience, and they complement each other with different methodologies.

Religion and Science Possible Relationships

You may feel more comfortable with one of these four approaches than the other three. My goal is not to convince you that any one approach is right, but to help you identify why one might seem more reasonable to you than the others, so that you can clearly understand not only how to express your views, but also how that view shapes the way you understand the opinions and approaches others may bring to the same question.

As we study different areas of science, we'll explore how different cultures responded to new theories. These "cultures" include not only the religious ideas of a particular time and place, but the existing scientific beliefs: sometimes the greatest opposition comes from those who hold to the current theory because they helped formulate or shape it.

Before we can really evaluate how science is perceived and received, we really need to understand what we mean by the term science. Our concept of science will determine whether new information is "scientific" or something else, whether it is good science or bad science, and whether we will use it to make moral, technical, or political decisions in the future.

Assumptions for this course

We make several assumptions in studying science, so that we at least start with a common framework. The most important ones for us at this stage are:

- Natural events have an objective reality. This means that natural objects exist, and natural events happen, whether or not we humans observe them or interpret them. For Christians, Jews, Moslems, and others who believe a Creator God, this is the direct outcome of having a created universe.

- Scientific explanations of natural events—theories, laws, hypotheses—are human constructions. Humans make up explanations (and excuses) about everything; scientific explanations have to follow certain rules.

- Scientific theories can change. If one explanation doesn't work, humans can make up another one, but the actual event remains unchanged by our explanation of it.

- Science is something all humans do. Science is a way of thinking about objects and events we observe, and it does not require expensive instrumentation or detailed mathematical analysis (although these are sometimes useful in refining our theories for testing).

You can learn to think and ask questions as a scientist would about natural phenomena, and you will be expected to do science during the course of this class.

Study/Discussion Questions:

- What is science? How has this term been used in the past, and what does it mean now?

- How do we learn about nature? How is scientific observation different from "just looking" at nature?

- What does it mean to know something? Is knowing a fact different from knowing (recognizing) a plant, or knowing a piece of music well enough to play it on an instrument?

- What do we mean by objective and subjective knowledge?

- What do we mean by essential and accidental properties?

- How is scientific knowledge different from other forms of knowledge or experience?

- How is a scientific theory accepted?

- How do conceptual frameworks influence our interpretations of our experiences?

Further Study/On Your Own

This section lists websites that are not required for answering homework or quiz questions, so reading whatever is listed here is optional.

- Check out the What is Science? site at the University of California at Berkeley, written to help teachers prepare high school students for college science courses. This site has many pages (see the Table of Contents page!), so you may want to bookmark it and come back to it as we talk about scientific methods.

© 2005 - 2024 This course is offered through Scholars Online, a non-profit organization supporting classical Christian education through online courses. Permission to copy course content (lessons and labs) for personal study is granted to students currently or formerly enrolled in the course through Scholars Online. Reproduction for any other purpose, without the express written consent of the author, is prohibited.