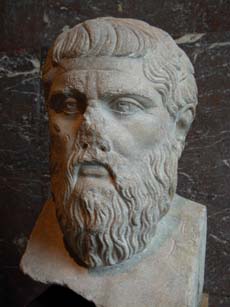

Photograph, © Copyright, Bruce A. McMenomy, 2010.

Week 14: The Philosophers

Socrates, ca. 470-399 B.C.

and Plato, ca. 427-347 B.C.

By class time this week, please have read:

- The Apology of Socrates.

- The “Allegory of the Cave” passage from the Republic.

- As much of the Meno as you can manage.

This week we come to Greek philosophical writing as embodied in perhaps its greatest stylist, Plato. My original intention was to provide some Plato, some Aristotle, and a little bit of Theophrastus (Aristotle’s other pupil beside Alexander the Great, and his successor as head of the Lyceum), but there just wasn’t time to include them all. Aristotle and Theophrastus will have to await another occasion — but I do recommend them both to you. Instead I would like to look at one of Plato’s most enduring statements of who and what he is, and a piece of another, while giving you a shot at the somewhat more difficult Meno if you’d like to dip into Plato’s epistemology (the study of how we know what we know). All are radically different — though all involve Socrates, and the Meno shows some of the reasons Socrates’ accusers were so annoyed with him (and indeed, Meletus was among those whose complaint brought Socrates to trial.)

Socrates is the central figure in most of Plato’s dialogues, and it is almost impossible to separate the two, save that we can say with some confidence that Plato presented a more charming Socrates than some others have done — probably more charming than he really was. Nevertheless, it is Plato’s character who has come down to the ages as the image of Socrates, whether accurate or not, and his approach to thinking about people is one of the foundations of Western culture.

The Apology is only marginally to be classed as a dialogue, since it is Socrates’ speech, offered at his (unsuccessful) trial for his life on the charge of “corrupting the youth of Athens.” Though called the Apology, you need to understand that this doesn’t imply that he’s sorry about anything — it is his defense, rather — an earlier meaning of the term “apology”. It is in some ways the Platonic manifesto — explaining to his contemporaries and posterity alike why he lived the way he did. It is a powerful piece of work that really requires no further explanation or justification. Read it thoughtfully. It should be a challenge.

Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Photograph © Copyright 2010, Bruce A. McMenomy

Then I’d like you to go take a look at the so-called ”Allegory of the Cave” passage from the Republic. The Republic is an exceedingly long dialogue, of which this is just an excerpt. This is one of the most potent extended allegories of all time, and you will find it referred everywhere to this day, both on account of its striking imagery and because of the message it conveys. It remains a particular favorite of Christian thinkers.

The Meno is one of the problematic dialogues in which Socrates asks an important question (here, “Is it possible to teach virtue?”), and professing to know nothing about the answer, but in which his interlocutor appears to know even less. It shows both his technique of aporia — “getting stuck” — and introduces more clearly than anywhere else the idea of anamnesis — the peculiarly Platonic notion that all knowledge is really recollection from a pre-existence. You will encounter this in the piece of the Republic that appears later. See whether this argument makes any sense to you; but also consider how he approaches the task of telling the tale. Plato’s dialogues are not poetic, but in other regards they are sometimes very good drama.

Consider for our discussion:

- Does Socrates seem to be making a serious appeal for his life, or does he consider the outcome a foregone conclusion?

- Do you agree with what he has to say about personal integrity here?

- The Allegory of the Cave is often taken as an analogy for any kind of spiritual life when it is contrasted with the physical world. How far are you willing to follow Plato in this regard?

- What do you make of the fact that the returning ex-captive is less persuasive, and also less able to see, than those who remain captive? Does that correspond with anything you know of in the problem?

- The Meno is largely an argument of the notion that knowledge is not so much discovered as remembered. Do you agree with that assessment? If so, why? If not, why not?

Concerning the Apology

Concerning the Allegory of the Cave (from the Republic)

Concerning the Meno

Contents of this page © Copyright 2001, 2003, 2006, 2010 by Bruce A. McMenomy.

Permission to print or reproduce this page is hereby given to members of Scholars Online for purposes of personal study only. All other use constitutes a violation of copyright.