Week 26: Gregory of Tours, 538-594

Hildebrandslied, ca. 800

By class time this week, please have read:

- The selections from Gregory of Tours’ History of the Franks.

- Auerbach’s Mimesis, “Sicharius and Chramnesindus”.

- The Hildebrandslied.

for Trinitarian Christianity in France.

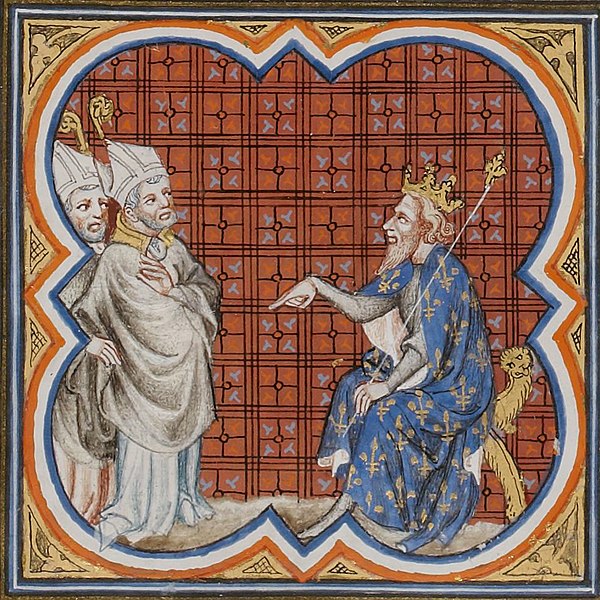

This week’s reading is a little something different — selections from Gregory of Tours’ History of the Franks. It will give you a chance to read something of the historical writing of the early Middle Ages. It’s a pity that you can’t read it in Latin: Gregory’s Latin is some of the most outrageous ever produced. Latin veterans may be shocked or amused to know that Gregory will use a genitive or accusative or dative absolute almost as freely as an ablative: he seems to have been under the impression that any case not otherwise being used in a clause was eligible to be pressed into service as an absolute. It’s historically completely unjustified, but it makes a certain kind of raw sense. The example in the chapter of Mimesis should suffice for most. If you’re interested in seeing more of the Latin text, it is available here at the Latin Library site. For all its technical faults, Gregory’s prose has a kind of quiet composure and narrative seriousness, written from the vantage point of a bishop in a tumultuous and difficult age; and it will give you access to one of the finest chapters in Auerbach’s study as well. Its value in a literary course may not be immediately apparent, but Auerbach’s chapter should help clarify how it means what it means.

It will probably be helpful to have a map at your disposal as you work through this — Gregory is recounting events from all over the Frankish kingdom.

Those who find this work terrifically interesting may want to read a more extensive selection of Gregory at the Fordham Medieval Sourcebook site, which has all kinds of fascinating material. Those who enjoy Gregory’s quirky story-telling but would rather read it from the comfort of a chair can get a complete and quite reliable translation in the Penguin Classics series.

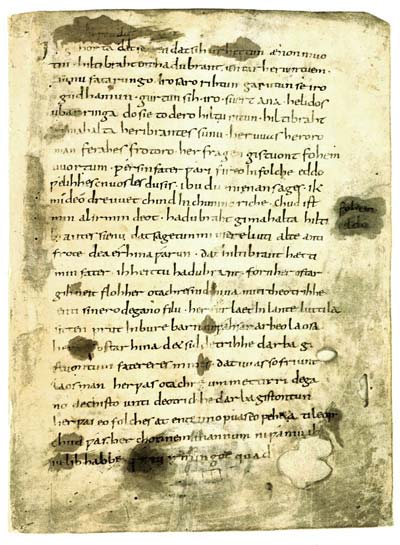

Finally, I’m asking you to read a poetic fragment that is all that remains of something that was probably not much longer, called the Hildebrandslied. (I have optimistically put the title into italics on the assumption that in its original form it represented something considerably longer.) This is written in Old High German, a language different from, but clearly related to the modern forms of German. A sample of the original language with its curious compound words is in the linked file. Its date is not entirely clear, but it probably stems from the period not long after Gregory was writing, though from further east. Both are Germanic cultures, nominally Christian, but the Hildebrandslied is not far removed from heroic pagan material: tonally and structurally, it may remind you more of Homer than of anything characteristically Christian.

Consider for discussion in class:

- What view is Gregory taking on the world around him, and how does it affect his writing? How does it compare with your view?

- What does Auerbach think of Gregory’s writing? Is he dismissing it as not being useful or valuable?

- How do you think the story of the conflict in the Hildebrandslied ends? There seem to be four distinct possibilities:

- Father kills son.

- Son kills father.

- The two kill each other.

- The two reconcile before anyone is killed.

usually considered the oldest surviving German poem.

This is the whole text.

Contents of this page © Copyright 2001, 2003, 2006, 2010 by Bruce A. McMenomy.

Permission to print or reproduce this page is hereby given to members of Scholars Online for purposes of personal study only. All other use constitutes a violation of copyright.