Week 34: Dante Alighieri, 1265-1321

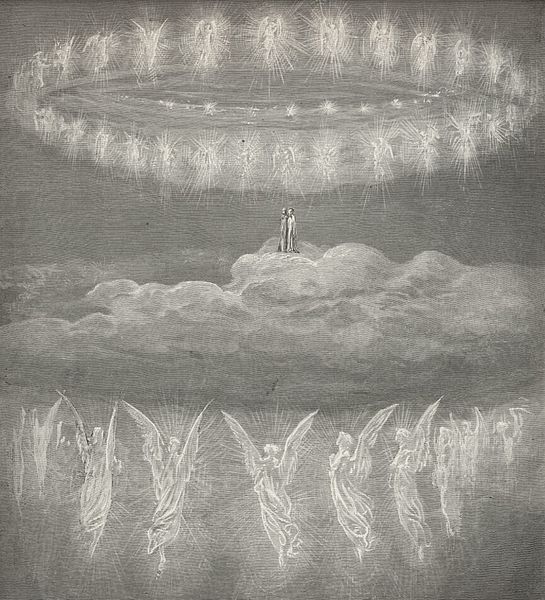

Paradiso

By class time this week, please have read:

- Dante, Paradiso

So we come to the end of our readings for the year. As both the Inferno and the Purgatorio were built around a classification of typse of sin, Heaven, untained by sin, is constructed around a typology of the seven main virtues. Once again we have a circular structure, but this time it is in an inverted form: the lowest and basest part is that nearest the earth, while the effective “center” — though not in a strictly geometrical sense — is what is outside. God is the center of the heavenly reality, of course, but in the physical arrangement of the cosmos, it is God himself, outside the Primum Mobile, who imparts motion and life to it. This is all, needless to say, inconsistent with modern cosmographical thinking, but reflects the widely-held Ptolemaic system of the world. Your book gives you enough explanation that you should be able to make sense out if it, though there are parts that are more mystical than comprehensible. The inversion of in and out is, I think, deliberate. For all that, however, circles and spheres proliferate throughout the work, and they form a systematic pattern that helps one keep one's bearings.

As Dante himself explains to Can Grande della Scala (following the Marchand translation) “Now it can be explained how the part offered (Paradiso) may be assigned a subject. Well, if the subject of the whole work, taken literally, is this subject: The status of souls after death, taken simply and not limited, it is obvious that in this part such a status is the subject, but restricted, that is, the status of the blessed souls after death. And if the subject of the whole work, taken allegorically, is man, as he gains or loses merit by the exercise of his freedom of will, being subject to the justice of punishment or reward, it is obvious that in this part the subject is restricted, namely, man, to the extent that he is subject by merits to the justice of punishment.”

The Paradiso has been seen as one of the more profound mystical pieces of writing ever produced, and at the same time, by others, an artistic failure. I am not going to tell you what you need to think about it: if it’s a moving experience for you, terrific. If not, though, certain practical points may help you bring it into focus at least somewhat. Arguably the task of the Inferno, vast as its scope is, is within the range of human perception. We are familiar with the contours of the fallen world, and all to aware of human evil. The same cannot be said of the matter of the Paradiso. Humans have only fitfully been given a glimpse of the beatific vision: we have no experience in this world of perfection or of absolute transcendence. What Dante is relating here is either the purest product of his own speculation or — if it was the real matter of a vision — still something for which human language is simply insufficient. Accordingly we experience one superlative piled atop another, until we wonder whether there is any way of grasping it.

On those terms, then, perhaps it is a failure; but then again, almost all art is ultimately a failure of a sort. If it is a failure, it's a most remarkable one, and one to which one can return again and again.

Taken as a whole, too, the Divine Comedy is an almost unexampled work of synthesis. In it Dante has woven together his insights about the spiritual life, about his personal anxieties and political fighting with his fellow Florentines, his love life as a child, the nature of good and evil, the construction of the universe, and a few thousand other things as well.

There are monuments to Dante all over Italy, and rightly so — not least in his native Florence. It is a curiosity, then, that in 2008 that he was finally granted a pardon on the charges that led to his exile from the city. I leave it to you to explore the layers of irony (and perhaps silliness) entailed in issuing a pardon to a man long dead who probably didn’t even want one, but whom the city had claimed for its own freely for the last five hundred years.

Contents of this page © Copyright 2001, 2003, 2006, 2010 by Bruce A. McMenomy.

Permission to print or reproduce this page is hereby given to members of Scholars Online for purposes of personal study only. All other use constitutes a violation of copyright.